Fetishised Merch

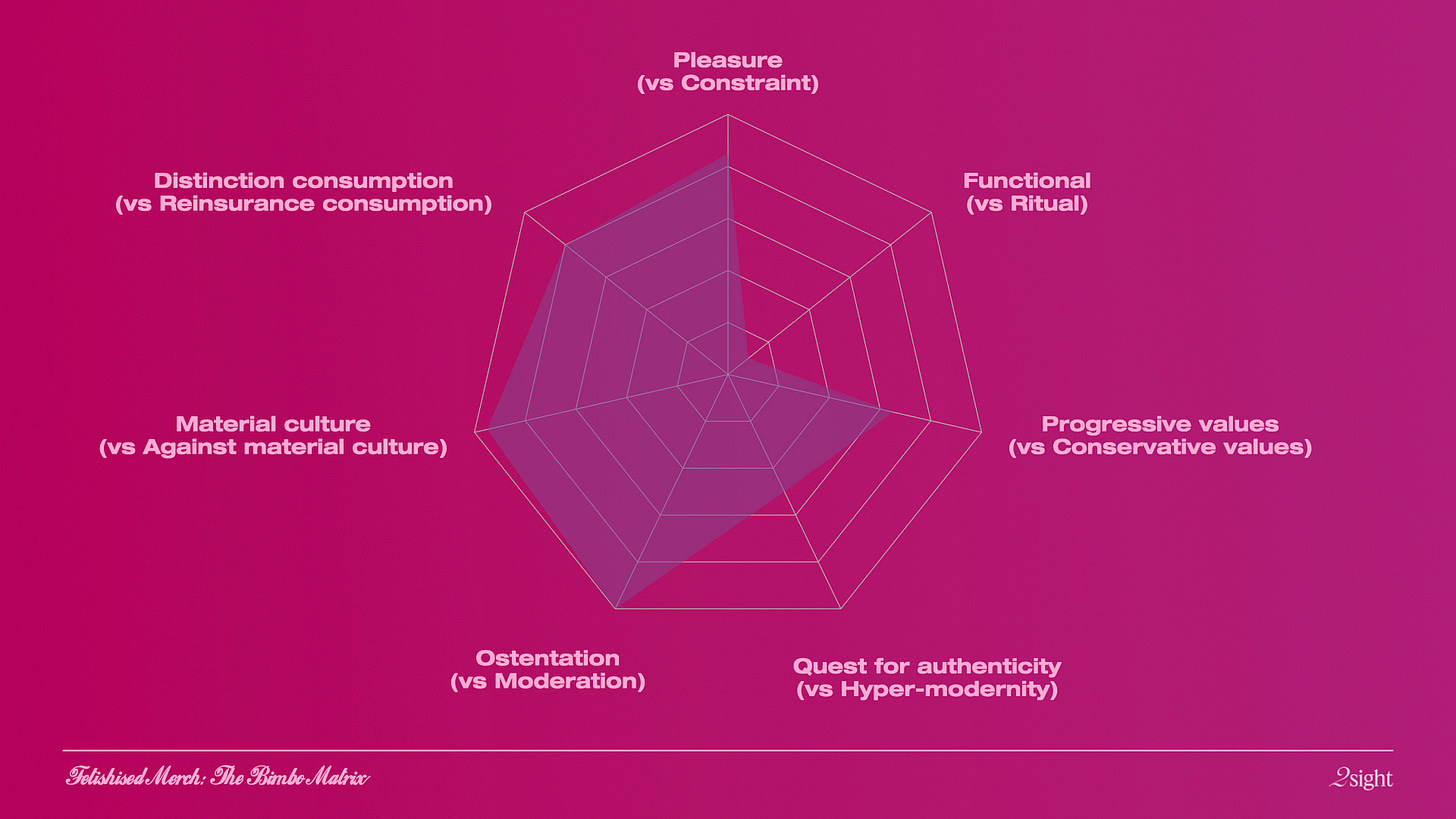

How is the Bimbo embracing hyper-consumerism, eschewing oppressiveness and navigating progressive femdom through positive fetishised merchandising?

Welcome to this auto-initiated cahier focusing on trends, foresight and cultural intelligence founded by 2sight, an independent foresight office based in Paris. Aside from forecasting future trends, deciphering consumer intelligence and crafting foresight strategies for our clients, we are taking this 2sight substack medium as a space for creative research, meaningful scepticism, and uplifting learning, where chaos gets enlightened and future trends are demystified.

Over the past few years, urged by influential and amplified voices, the rewriting of narratives around gender, femininity and female representations is a cultural work in progress.

For more context, our bipolar world and antagonistic societies have left enough space for opposing oppressive-versus-liberative conditions to prosper: on one hand, women’s right to control their own bodies is no longer a given claim, but on the other hand, ultra-femininity makers are unprecedentedly unbridled. Anecdotally, the exact same society that limited (or let’s use “revoked” here as an appropriate verb) fundamental access to abortion also produced an “euphoria-based” teen drama TV series paying tribute to young women trying to establish their identity through sexiness.

Market snapshot:

60% of global citizens believe that gender equality has progressed over the last quarter-century, but almost the same number of women (57%) report having experienced some form of gender discrimination in their personal, professional, and public lives. (“Global gender equality survey” by Focus 2030 and Women Deliver, 2021)

Paradigms are shifting, from sex to bimbo’s sexiness: “We may have collectively lost our libido, but fashion certainly hasn’t: skirts are getting shorter, boots higher and shirts are disappearing all together.” (The Face, 2022)

According to shopping app Lyst, searches for “see-through” clothing pieces have gone up 63% since 2021, while male shoppers’ desire for cropped items has increased by 21%. (Lyst, 2022)

In 2021, surgeons “detailed an enormous increase” (up from 42% in 2017) in people wanting procedures, with 77% of surgeons surveyed reporting “wanting to look better on selfies” as a key motivating factor for procedures. (American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 2021)

As of writing, the #bimbocore and #barbiecore hashtags have respectively accumulated over 34 millions and 27 millions views on TikTok. (TikTok, August 2022)

Woman as such and her representations, through collective imaginaries and pre-established lifestyles, endured a commodification process where femininity turned into a merchandise. In this context, the Bimbo figure and her mythology are being harnessed as a positive fetish to embrace hyper-consumerism, eschew oppressiveness and navigate progressive femdom.

HYPER-FEMININITY:

A CONSUMERISM’S TOTEM

In our living hyper-consumerism realm, it all starts with marketing and its experts mastering the art of establishing and shaping personae or typology frameworks acting as portraits of the typical consumers. This process of stereotyping human beings obviously serves an ultimate goal: selling pre-established lifestyles that our performance culture inclines to conform by.

And just like that, human figures — and more specifically women as per our current subject of interest —, with everything entitled to identities and bodies, are commodified. Already in 2007, the online game Ma-Bimbo (“My Bimbo” in English) went beyond promoting the perfect go-to bimbo starter kit by stimulating a pre-established lifestyle and offering a chance to its 20k players to experience life as a bimbo: “[In Ma-Bimbo game], the goal is to become the most beautiful. The bimbo can go out with boys (called ‘boyfriends’), buy clothes, do two cosmetic surgeries (face and breast implant procedures), get multiple tattoos, put on make-up, change her hairstyle…”

Let’s drop it out: the persona of the Bimbo became a totem for all things hyper-feminised, as induced by consumerism culture. On the “totem” matter, the official definition from Oxford Languages states:

Totem /ˈtəʊtəm/

noun: totem; plural noun: totems

a natural object or animal that is believed by a particular society to have spiritual significance and that is adopted by it as an emblem.

a person or thing regarded as being symbolic or representative of a particular quality or concept.

French organisation CNRTL (the National Centre for Textual and Lexical Resources) details the etymological nature of a “totem” rooted in the 1609’s edition of Lescarbot’s “Histoire de la Nouvelle France” (“History of New France” in English):

“A totem serves as the emblem of a family, tribe, or nation.” (CNRTL)

In other words, the Woman and her (hyper-)femininity through the figure of the Bimbo have been commodified to socially reach a totem status to crystallise all the femdom’s symbols awarded by our nations and societies. A totem just like Eric Dickes’ Vitruvian woman, a sculptural representation of the ideal woman as a Barbie.

Under the influence of a consumption culture familiar with producing totems, femdom’s situation has been reversed: paradigms shifted from Woman to a new symbolic meaning coloured by the merchandisation logic. It is no coincidence that the social woman has been globally celebrated every year since 1910 on March 8th for the space of a day… to finally come back to its commodified condition on March 9th with the annual national Barbie Day. Business is catching up with social reality.

If another proof of the victory of the merchandising orthodoxy over social representations of women is necessary, history drew a comparison between economic health and the objectification of women bodies as a remedy to dark thoughts:

Theorised in 1926 by economist George Taylor, the Hemline Index establishes that “the length of women’s skirts and dresses can be indicative of the direction of financial markets. Meaning, hemlines rise in times of economic prosperity and elongate when the economy slows.” ("How the Hemline Index predicts fashion’s future" by Sophie Shaw, editor in CR Fashionbook, 2020)

In 1987, The Wall Street Journal claimed the year of the Black Monday stock market crash, but also “crash or no crash, it is certain that 1987 is the year of the Bimbo,” “everybody’s favorite epithet.” ("The Bimbo’s Laugh" by Marlowe Granados, writer and filmmaker in The Baffler, 2021)

Nowadays, these former representations of merchandised female portraits have become more ironic as the Hemline Index has been reversed: trends are indicating that skirts and dresses are getting shorter as a way to assert the illusion that “everything is okay”.

The Bimbo — which evolved from Barbie to Lolita to Bimbo — now acts as the key totem for dealing with uncertainty and political oppression.

Definition of the Bimbo and her iterations:

Bimbo (also found under names such as ‘cagole’ or ‘Essex girls’ depending on the region where she lives): a young woman considered to be attractive but not intelligent. (Collins English Dictionary)

Himbo: a portmanteau of the words ‘him’ and ‘bimbo’, is a slang term for an attractive but vacuous man. (Merriam-Webster)

Thembo: (slang, sometimes derogatory) a physically attractive non-binary person who lacks intelligence; the non-binary equivalent of a bimbo. (Wiktionary)

“Not intelligent”, “vacuous”, “lacks intelligence”... No need to be said that the Bimbo persona has never been awarded as a hero by the collective unconscious — at least, not till today. If she is the ultimate totem of hyper-consumption, she is also pointed out and mocked as the fiendish scapegoat of the same society that produced her cliché.

“Object of mockery and fantasies, the cagole [the South-of-France version of the Bimbo] lives in a complex space, which rejects precisely when it desires.” (Alice Pfeiffer, author of “Je ne suis PAS parisienne. Eloge de toutes les françaises” book, 2019)

As per Elle Woods’ famous quote in the Legally Blonde film: “You're breaking up with me because I'm TOO... BLONDE”, the Bimbo is precisely rejected because she perfectly embodies an on-point caricature of the “too much”, of the hyper-consumerism doctrine we collectively built and agreed on.

“Too blond or too brunette or too red, multicoloured, embellished from head to nails, too low-necked, tanned, loudmouth, tattooed, too kooky, too everything… The Bimbo is the superlative of a woman who reminds others that too much is not enough…” (Sébastien Haddouk, film director of “Cagole Forever”, 2017)

POSITIVE FETISHISATION:

PLEASURE OVER OPPRESSION

Years post-MeToo and post-endured-fetishisation (just to name only one example of this is the 1.9 millions members Facebook group “Garde la pêche” that documents female nudity by posting sexy photos of buttocks — mostly taken without the consent of the female protagonists), the media have proclaimed the years 2021 and 2022 as “the year of the Bimbo”. And it is already supposed to be continued in 2023 with the release of Greta Gerwig's “Barbie” movie or the launch of the SpaceX-themed Barbie.

Bimboism is making a come-back then. But this time, the Bimbo is wearing a more heroic costume under designation such as “New-age Bimbo”. With Gen Z coming in after the explosion of over-consumption and mastering its threats — notably the dispossession and commodification of the body — bimboism is unlocked as the antidote to oppression. For this generation, it is now a matter of taking back ownership (and control) of one's body by celebrating, with irony, its potential commodification through the aestheticization of the 2000s bimbo pop icons.

“The bimbo aesthetic is making waves and also highlighting — in a loud color — how feminism, diversity, and even global politics intersect [...] it's an extension of these generations calling for diversity and inclusion.” ("Barbiecore: the Gen Z and Millennial fashion statement on feminism" by Marguerite Ward, journalist in Business Insider, 2022)

The script of stereotypes is flipping. A mechanism of positive fetishisation is undergoing as a pleasure-enabler over oppression.

In this context, Balenciaga pays homage to the “cagole” and Italian fashion house Blumarine — self-defined as “a wild rose garden of femmine bellissime who show their strength by being soft, and flaunt their romanticism by being tough” — rises again for the ashes. Its last SS22 campaign “That was mine” jumped head first in this pleasure-seeking bimbo quest by promoting an “irreverent message [...] declined in a distinctly glamour key.”

If this New-age Bimbo is reclaiming fetishisation to counter the “Male Gaze” theory coined by Laura Mulvey, we could however criticise the fact that those new representations are built according to this exact same sexualising male-dominated gaze, as they fall against the dominant “mother or slut” archetype. Again, here it is a matter of stripping a fetishisation of its endured oppressive character, just as we do with sexual fantasies:

“Maybe we just need to picture ourselves as cute sluts happily wallowing in the male domination’s mire, because it's too exhausting trying to constantly avoid its splashes [...] The active research, through imaginaries, of the violence we are constantly threatened by aims perhaps to neutralise this domination, to subvert it.” (Mona Chollet, author of “Réinventer l’amour” book, 2021)

Instead of running away from oppressive situations to pursue pleasure in other territories — a basic human mechanism described by Henri Laborit in his essay “L'Éloge de la Fuite” —, the Bimbo embraces, and therefore actively confronts them.

“Bimboism does not necessarily require passivity. [The bimbo] pursues hyper-femininity to the extreme — at times to the point of drag. She’s glossy, voluminous, and kind. The bimbo counters the assumption that we would opt out of femininity if we could; in fact, she embraces it.” ("The Bimbo’s Laugh" by Marlowe Granados, writer and filmmaker in The Baffler, 2021)

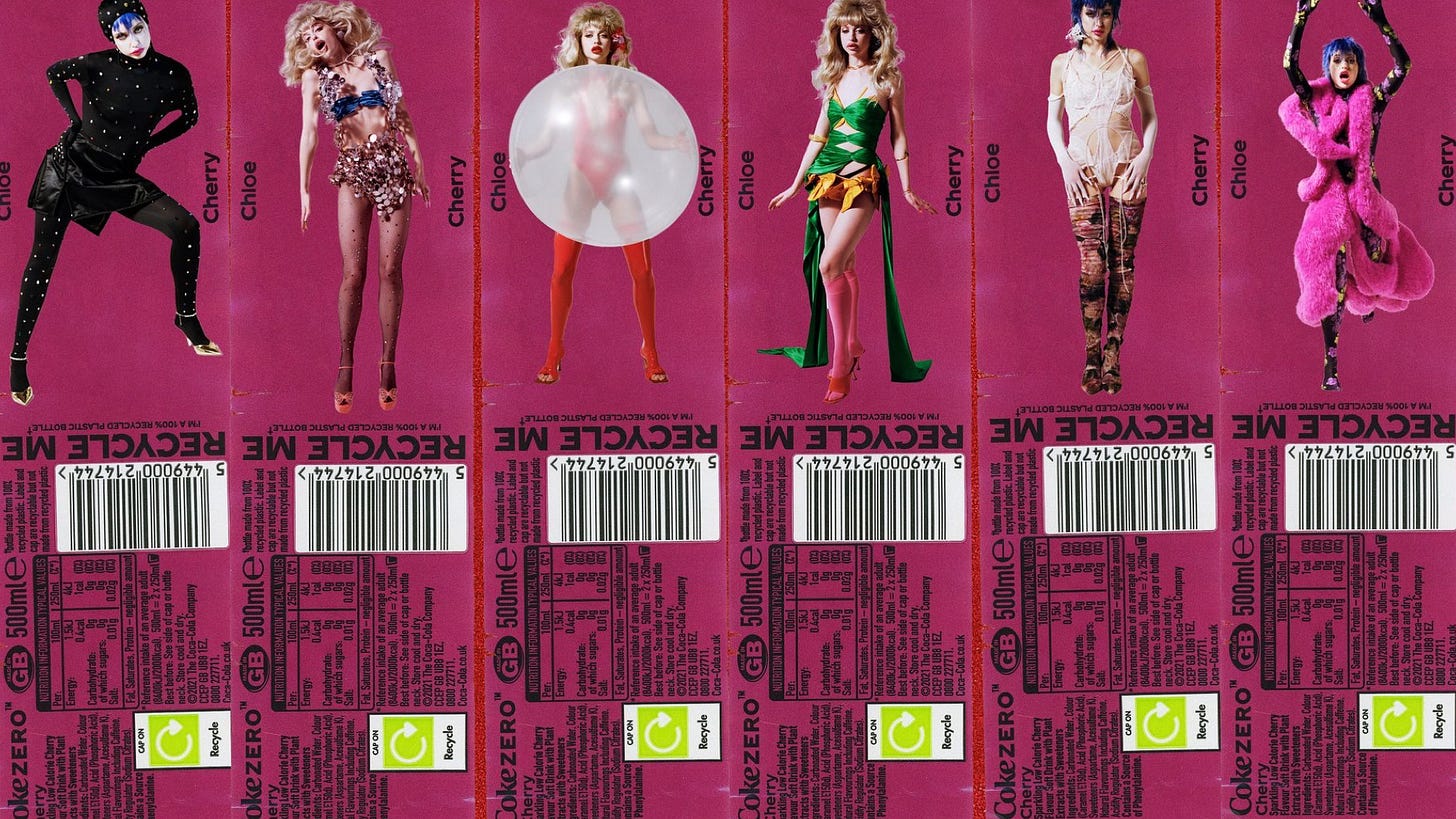

In this quest of fetishising femdom to reclaim body representations and its vernaculars, a culture of extravagance paired with ultra-gendered aesthetics labelled as “Barbiecore”, “Bimbocore” and “Slutcore” is emerging:

After all, the cultural evolution of the Bimbo figure and her visual codes seem to signal a significant shift in consumption behaviours, which might even grow further in the future. Since marketing has the power to produce objects of fictions that blur boundaries between necessity and pleasure — an ability that our rather moralistic and radical current political institutions and social movements lack —, we now live in an era where consumer communities harness positive fetishes, such as the Bimbo, for politicised and militant purposes.

POST-FEMME:

AUGMENTED COMMODIFICATION

So far, we’ve already established that portraits of women were commodified and promoted by marketing’s ins and outs as representative totems, allowing consumers to project and identify themselves to those femdom’s socio-styles. We also formulated that today’s bimboism was unlocked by communities as a statement tool to find emancipation from cultural clichés, via the adoption of those same hyper-consumption’s exaggerated stereotypes.

What’s next for women's representations, for bimbos and female expressions?

We are now entering an era we call “Faked Authenticity”, where boundaries between the physical and the digital, between authentic bodies and faked bodies are unprecedentedly blurred, even erased. As if we’ve already managed to overcome all consumption opportunities that our “real world” offers, consumerism is now augmented in new extraordinary realms. The same process applies to commodification: algorithms made their entry as the new kings, codifying and defining our next women’s totems and fetishes.

Among these new realms of augmentification, the web 3 is promising unbridled creativity and “a new decade of tremendous value creation where ideas and innovations will become more valuable” (according to businessman Mukesh Ambani). Yet, nascent meta-universes are already suffering an imaginary crisis where the reproduction of hyperrealistic worlds prevails over envisioning environments and representations we never imagined or met so far. And before they even emerged, those web 3’s realities are already inhabited (and led) by one archetype:

“The archetype most commonly associated with Web 3 is the tech bro, a man who is ‘bullish on crypto’ and at best, flush with cash, but lacking cultural capital.” (“Web3 needs more bimbos” by Tara Kenny, culture writer in i-D, 2022)

“Web3 needs more bimbos” titles i-D. Consumers seem to agree. After using the Bimbo as a powerful figure to counter IRL oppression, they are expressing a similar quest when it comes to the metaverse:

According to the Institute of Digital Fashion’s 2021 study “My Self, My Avatar, My Identity”, people surveyed asked for more diverse representations in new online spaces, since they judge that what’s currently available on the matter isn’t actually sufficient. (“My Self, My Avatar, My Identity” by the Institute of Digital Fashion, 2021)

The representation of women, their bodies and femdom beyond commodified totems in the web 3 is already a key rising question. As per today, web 3’s algorithms, developed according to the IRL’s male gaze, are already reproducing human bias and giving birth to augmented female fetishes (this time not yet harnessed to counter oppression).

Aligned with this interpretation, micro-website Femme Flipbook by Imogen Fox explores the possibilities of post-human beauty standards, intending to challenge the epitome of post-femme representation.

As the web 3 develops, it then becomes a new space where fighting against endured and oppressive women fetishisation is necessary: “as creators, we are responsible to offer a new world where female gamers will feel comfortable” says artist and interaction designer Mélanie Courtinat.

We might not come yet with a clear answer of what the post-femme situation should be in the web 3, but “crypto-queens” and “web 3 bimbos” are already emerging as early manifestations of this. Paris Hilton has extended her 2000s bimbo status into new realms by hosting parties in the metaverse, and Azealia Banks has released her audio sex tape as an NFT.

“This new self-aware, cyber femmebot has the potential to revive a Web 3 culture that was dead on arrival.” (“Web3 needs more bimbos” by Tara Kenny, culture writer in i-D, 2022)